“Dezastru,” the only other person on the platform at Copşa Mică's train station said to me, while somberly shaking her head and gesturing to the buildings across the rails. It's not a word that needed translation; I'd only been here for an hour and already I could feel the pollution - a sulphuric, sooty taste - lacing my throat. I'm sure I could feel it in my lungs too. And this place was cleaned up 20 years ago.

Why did Copşa Mică become so polluted? How can living standards be improved? Is pollution the only problem? Is there any hope for the town that once made international headlines, but now lies forgotten? Read on...

Shell of the former Carbosin factory, Copşa Mică

Quick links: Why? | Everyone is Ill | Romanian Revolution | Today | Future?

Why Copşa Mică and Pollution?

Plenty of other former Communist Bloc countries suffered at the hands of rapid industrialisation, but why did Copşa Mică (pronounced COPE-shah MEE-kah) in Transylvania become so infamous, with 1990s UK newspaper headlines such as "The Town Where Everyone is Ill" and "The Most Polluted Town in Europe"?

There was already industry in Copşa Mică in the 1930s, but when Romania became a Soviet satellite in 1947, Stalin-esque rapid industrialisation (using outdated British technology) followed, with little concern for the excessive pollution and waste that would arrive in the longer-term, as experienced during Western Europe's Industrial Revolution over a hundred years earlier.

Nicolae Ceauşescu

The most absurd of all the totalitarian governments of this century's Europe.

In the mid-1960s a man responsible for "the most absurd of all the totalitarian governments of this [20th] century's Europe", Nicolae Ceauşescu, became Romania's head of state.

During Ceauşescu's reign heavy industry was located in a number of small areas to concentrate pollution rather than spread it over a wider area (hmmm, I remember doing something similar on the Sim City game many years ago, though I did add tree buffers between residential and industrial zones). Copşa Mică was chosen as one of these locations despite being geographically inappropriate, with its location in a valley beside the Tarnava River. The regime were fully aware of their actions; farmers were banned from selling their produce outside of Copşa Mică to limit the spread of toxins and factories were built with short smokestacks to keep emissions in the valley.

By the 1970s the woodland, fruit trees and corn fields that covered the hills surrounding the town had fallen prey to the devastating effect of the pollutants, the two biggest being the Carbosin factory, which produced a black powder used as colouring in the production of rubber, and Sometra, a processor of non-ferrous metals.

Top and chimneys of the Sometra factory, as it stands today

Romania was falling deeper into debt, so to avoid taking out more foreign loans Ceauşescu demanded increased production while allowing the already antiquated industrial plants to fall into disrepair.

In 1981 he introduced an austerity program to try and help Romania liquidate its $10 billion debt (which sounds like pennies compared to the debts of some countries these days, including the UK, and Romania again). Essentials such as heat and food were heavily rationed, further reducing the standard of living in an already poor country.

Crazy Amounts of Pollution and the Securitate

On occasions lead emissions in Copşa Mică exceeded the international limits 1000 times over, for a time over 10 tons of carbon soot were released into the atmosphere every day, and until recently the toxic element cadmium still existed above legal limits in the area's topsoil. Under the communist rule such statistics and the effects of the pollution were state secrets, helping prevent international intervention while keeping locals in the dark.

By the mid to late 1980s the Romanian Securitate (secret police) had become ubiquitous, with over 10,000 employees and an estimated half a million informers. If residents complained about pollution it was seen as a criticism of communism.

Free speech was restricted and opinions that didn't favour the Communist Party were forbidden.

More remains of the Carbosin factory

Everyone is Ill

In a country that already had one of the highest infant mortality rates in Europe, Copşa Mică had a life expectancy 9 years below the Romanian average. By now common ailments afflicting the town's residents included (and still do):

- lead poisoning

- bronchitis

- ricketts

- finger-twitching

- learning difficulties

- impotence

- asthma

- stunted growth

- depression

- alcoholism

As well as the direct effect of pollution from the industry, the likes of lead and cadmium were being ingested from locally grown produce, with many residents unable to afford food and milk from elsewhere.

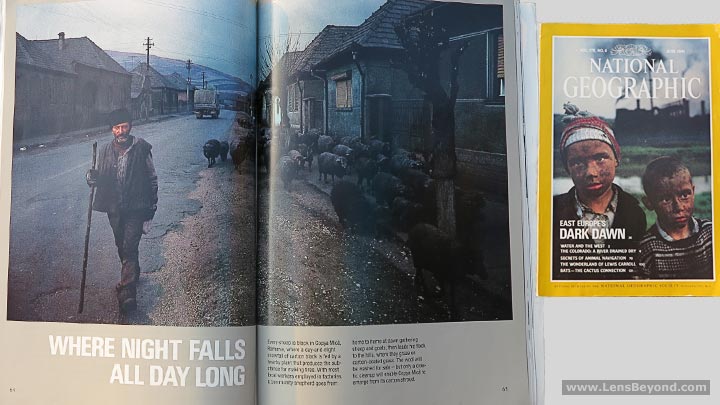

There was a time when Copşa Mică was home to numerous horses, but the only farm animals able to survive in this bleak environment were sheep, all black from the soot.

The Romanian Revolution of 1989

Nicolae Ceauşescu's government was overthrown in 1989 after he was captured while on the run with his wife, who happened to be the Deputy Prime Minister. They were charged with offences including genocide and executed on Christmas Day. The Communist Party of Romania was outlawed the following month, and as more foreign journalists began to visit Romania, the infamy of Copşa Mică and its status as Europe's most polluted town began to spread.

Nobody knew about us. Now people come, and they say we are the most polluted town in the world.

In the New York Times local health worker Dr. Alexandru Balin was quoted as saying "Nobody knew about us. Now people come, and they say we are the most polluted town in the world."

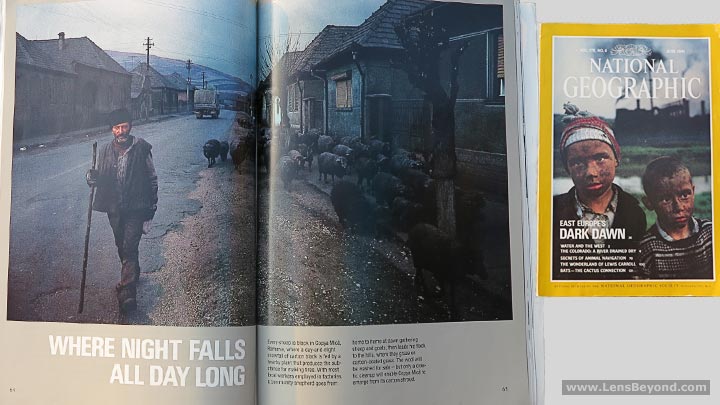

Copşa Mică even made the front cover of National Geographic magazine in 1991.

With the pressure of international media attention some sections of the polluting Carbosin plant were closed almost immediately, though two years later in 1992, the health risks at the Sometra metallurgical factory were still considered so high that the retirement age was 45 years, compared to 62 nationally.

Associated Press reported that workers acknowledged the problems, but that it would be disastrous to close the factories due to the 3500 local people (around 50% of the population) they employed.

The Carbosin factory closed completely in 1993, and most international media disappeared. With its limited visual impact compared to Carbosin's black soot, Sometra continued to cause irreparable damage to the town's residents, and arguably was the biggest problem all along.

Copşa Mică in 2013

"The town is really a dangerous place to live - everything you touch, everything you eat, the air you breathe is serious for your health." said Professor Doru Banaduc from the University of Sibiu in 2007.

A lovely little church in Copşa Mică, only a few hundred metres away from the Carbosin factory

In 2013, away from the shell of the old Carbosin factory, the town looks as clean as any other. New trees have been planted in the valley (though many haven't survived) and nature has begun to reclaim the still-black industrial site. But as I mentioned, the sulphur dioxide still laces the air. Locally grown produce is still poisonous and health advisors advise against eating or drinking it.

"It took seven years to clean Copşa Mică" says the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. They even add a positive spin by quoting a woman who is happy that she can now hang washing outside to dry. Despite how bad Copşa Mică was, I wouldn't call that clean-up a success story.

Only 5 years ago the Blacksmith Institute reported that "96% of children ages 2-14 have chronic bronchitis and other respiratory problems."

Chantal Maas, who is leading a project to improve the future of Copşa Mică, was kind enough to speak to me about the town. Although she's from Transylvania, she is not from Copşa Mică, so I started by asking her why she decided to get involved, followed by a question about the current conditions for farming.

“After having lived in Poland, in Oswiecim (which the Germans infamously called Auschwitz) and by visiting the old IG Farben factory, I remembered seeing Copşa Mică during the time of Ceauşescu. I decided it all had to change.

Also, the battle of the Mayor to give colour to his city. There was a fight with Bucharest, just to get paintings. Residents are used to living in a grey/black world, and didn't want to change. This led to me getting involved.”

Every day they eat the vegetables and poison themselves more. The low level of income leaves no other choice.

IG Farben was a cartel that was once the largest chemical company in the world. They were charged with war crimes that occurred during World War II.

“Many people in Copsa have a small garden where they grow their own vegetables. Especially for those people closest to the Sometra factory, the soil is heavy metal contaminated. Every day they eat the vegetables and poison themselves more. The low level of income leaves no other choice. Sale elsewhere is prohibited.

For ourselves we find food from Medias on the market.”

While other locations mentioned in the 1991 National Geographic article, such as Poland's Nowa Huta (which I also happen to have visited, a massive old factory is now a concert venue) bare little sign of their dirty past, Copşa Mică seems to have been forgotten. The pollution from Nowa Huta's steel factory was so bad it melted sculptures in Krakow 10 miles away. Krakow's own Vistula River was so polluted by the early 90s that the water was too dirty to use for its own industry. Budapest, the capital of Hungary, suffered from such thick smog, at times it was barely possible to see across the banks of the River Danube, between the two halves of the city - Buda and Pest.

Copşa Mică in the June 1991 issue of National Geographic The same scene in 2009 via Google Street View

The same scene in 2009 via Google Street ViewDespite lying on one of Romania's main train lines, perhaps Copşa Mică has been forgotten because it's away from the eyes of tourists, being 30 miles from medieval Sighişoara in one direction and Sibiu (European Capital of Culture in 2007) in another. Or maybe Romania just doesn't have the money; based on GDP per capita it's one of the 10 poorest countries in Europe, and according to the CIA Factbook, 21% of the population live below the poverty line. In Bucharest, the capital city, the city centre itself has many rundown locations you might expect to see somewhere with Copşa Mică's reputation - and according to a study in 2011, Bucharest has the highest air pollution of any city in Europe. "The most polluted town in Europe" isn't Romania's only problem.

When they hear 'Copsa', they hang up.

After dealings with local mayor, Tudor Mihalache, and the Romanian government, I asked Chantal Maas for her own (much better informed) views.

“On several occasions I have contacted the (then) Minister of Environment in Bucharest. When they hear 'Copsa', they hang up. There is no political will to clean up. When MPs have pushed for a clean-up, it has not won them votes.

European Commission funds are available, we have seen an agreement with the municipality - but without the approval of Bucharest it is impossible to obtain EU funds.

There is a problem, a solution, European funds...The European Commissioner [President José Manuel] Barroso does not have the power to unlock the deadlock.

In the case of Copsa the "polluter pays principle" is not applied. There are two polluters; the Romanian state and then Sometra. It is impossible to contact the Greek owner of this factory.

Only a media scandal could unlock the file. At this stage no journalist is interested. Without a sponsor or a media campaign, the cleanup will not be done.

We could combine two other dossiers. Namely Rosia Montana (a gold mine exploited by an unsavory company located in Canada), and the exploitation of shale gas (elsewhere in Romania).”

Nature is already reclaiming parts of the Carbosin factory

The local economy is moribund.

Experts say it could be decades before Copşa Mică can be considered completely safe to live in again, but along with continuing health problems, the latest issues to beset the town are unemployment; around 1000 workers have been made redundant in recent years at the Greek owned (since 1998) Sometra metals factory, the reasons given: initially modernisation and the economic climate, but eventually just the economy as the factory closed completely.

"The smelter used to pay for [via taxes and donations] running water, public lighting, emergency care and Christmas gifts for children, plus a re-forestation programme," said Copşa Mică's mayor, Tudor Mihalache, after the closure.

I asked Chantal Maas if any new jobs had come to town since Sometra's closure.

“The local economy is moribund. Some young people have found employment in supermarkets in nearby Medias. Others leave.”

The Future of Copşa Mică?

Next Chantal Maas spoke about the plans for the future of Copşa Mică, which will only happen if the previously mentioned deadlock regarding the Romanian government and EU funds can be broken.

A clean industry based on bamboo can revitalise the region.

“One idea has established itself: bamboo. Studying its potential I learnt it has a high power of soil remediation. The link: bamboo to Copşa Mică, was done.

We can clean the most polluted town in Europe with giant bamboo grasses and make a town with a twenty-first century industry. It's simple to set up and the least expensive. Subsequently a clean industry based on bamboo can revitalise the region.

The project is very complete. When the bamboo plants have absorbed the heavy metals from the soil, they must be destroyed. A biomass plant should be installed. This plant could use the waste from the area (Blaj, Medias etc.) and would also create jobs.

Once the soil is clean, for future industry, bamboo is a good alternative to wood.”

Circulate information.

Finally I asked if there is anything visitors or outsiders can do to help Copşa Mică.

“Circulate information. Help us find a TV station/documentary maker wanting to do a story.”

So, spread the word. It would be a great story if Copşa Mică could recover and turn into a prosperous, thriving town. One day, hopefully journalists will return for positive reasons. I'd love to hear what you think - add your comments below. There are also details for getting to Copşa Mică below.

I'll keep this page updated with any developments. For further reading and directions to Copşa Mică see below.

Like it? Hate it? Impartial? Share it!

Further reading

There's a chapter on Copsa Mica in Reporting Live from the End of the World by David Shukman (who has since become Science Editor for BBC News).

by David Shukman (who has since become Science Editor for BBC News).

I wonder where the next Copsa Mica will be as similar things happen in China and other developing countries. The future of Rosia Montana, another town in Romania, could be looking bleak, and unfortunately there are plenty of other contenders. Us humans never learn...

Sources not linked in text:

Satellite image from One Planet, Many People: Atlas of Our Changing Environment

Eastern Europe Struggles to Purge Security Services

Influence of environment on population health in Copsa Mica

Trial and Execution: The Dramatic Deaths of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu

Financial crisis divides EU on greenhouse gas cuts (PDF)

How to get to Copsa Mica

If you'd like to visit yourself, Copsa Mica is on the main train line between Sibiu and Sighisoara, a 45-minute journey from either city. The abandoned industrial plant is right next to the train station and trains run every hour or two, which is plenty of time to have a wander around the factory, although it's worth staying for longer to see the churches and memorial in the town, along with the fortified church just outside the town, Asszonyfalva.

View from Copsa Mica's train station

Sighisoara and Sibiu are both great places to visit; the former has a small but perfectly formed old town, and Sibiu was the European Capital of Culture in 2007. Although I didn't visit, Medias is only 10 miles away and looks to have a picturesque medieval town centre.

Back to top ↑

by David Shukman (who has since become Science Editor for BBC News).

Comments